Alexander the Great and the Secrets of Zeus-Ammon

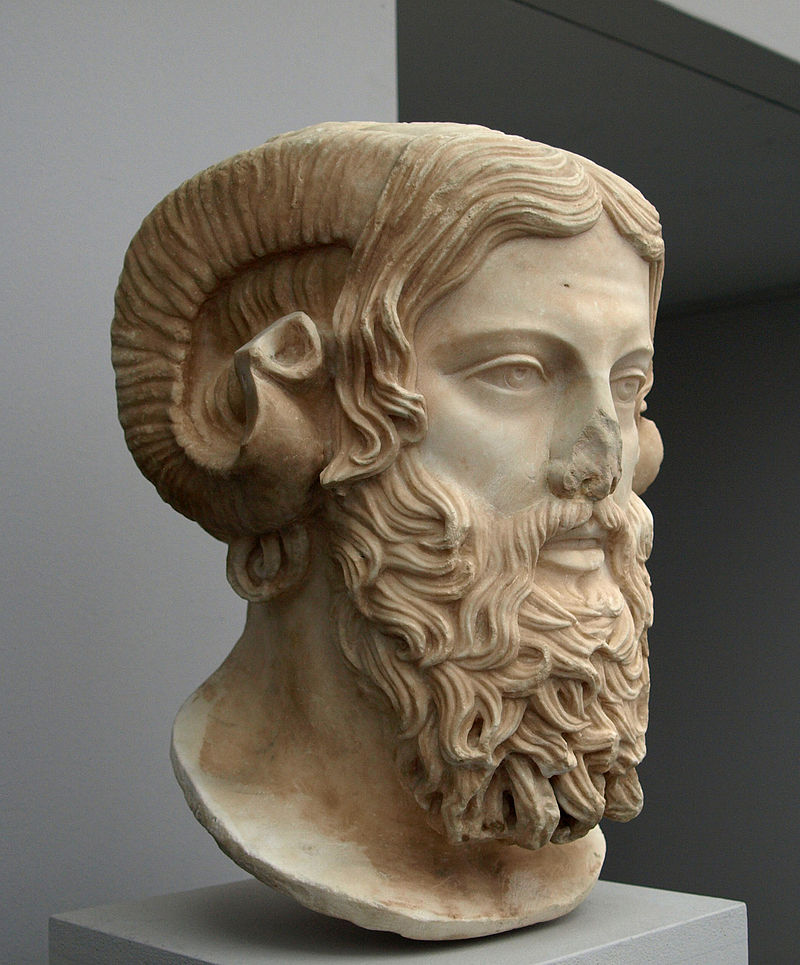

A Roman copy of a Greek sculpture of Zeus Ammon. The original dated back to the late 5th century BCE.

Alexander's relationship with the ancient deity known as Zeus-Ammon is one of the great mysteries of his life. This article will use the ancient evidence and modern analysis to try and separate the truth from the myth.

First off, who was Zeus-Ammon?

Zeus was considered the ruler of the Olympian gods in ancient Greece and Macedon. Amun, called "Ammon" in Greece, was the parallel "king of the gods" in the religion of ancient Egypt.

Unlike many religions, the religion of ancient Greece was capable of incorporating foreign deities into their belief system. A god could take on different forms depending on the place and circumstances. By Alexander's time, Zeus-Ammon was a well-known deity in Greece - basically a hybrid of these two chief gods.

This hybrid god called Zeus-Ammon had an oracle who was located deep in the Libyan desert, a few hundred miles west of Memphis, the Egyptian capital city. The oracles of antiquity were prophets believed to possess a unique connection to the gods. This connection allowed them to forecast the future, which was an ability in especially high demand among the great royals and warriors of the day. Alexander the Great was no exception.

This Oracle of Ammon was located in the Siwah Oasis - a 50-mile stretch of trees and vegetation found deep in the northern Sahara desert. Siwah had first become an important sacred site in the Mediterranean world in the 7th century BCE, three centuries before Alexander's time. It was widely believed by that time that the Greek mythological hero Heracles (and probably Perseus) had made a pilgrimage there to consult Zeus Ammon. Alexander, a student of the lives of the mythological heroes, knew these stories.

A panorama of the Siwah Oasis and surrounding desert

An Odyssey in Libya

In 331 BCE, after successfully reaching Egypt and "liberating" its people from Persian rule, Alexander and a small group of followers embarked on his own desert excursion to speak to the famous oracle. According to Oxford historian Robin Lane Fox, this trip represented the "strangest strand in Alexander's life and legend" (Alexander the Great, 201).

It's regarded as strange for a couple of reasons: (1) it represents one of the few times Alexander seemed to make a detour to a place with no obvious strategic significance to his campaign, and (2) a variety of supernatural legends and rumors came out of the trip that continue to puzzle historians today.

Alexander's path to Siwah was quite dangerous. Here is Plutarch's description, from The Life of Alexander:

"This was a long and arduous journey, which was beset by two especial dangers. The first was the lack of water, of which there was none to be found along the route for many days' march. The second arises if a strong south wind should overtake the traveller as he is crossing the vast expanse of deep, soft sand, as is said to have happened to the army of Camyses* long ago: the wind raised great billows of sand and blew them across the plain so that 50,000 men were swallowed up and perished" (309).

*Camyses was a Persian king of the 6th century BCE, whose army was allegedly wiped out by a sandstorm on their march to Siwah. This story, however, has been disputed.

Rolling sand dunes outside of the Siwah Oasis.

So how did Alexander's group reach Siwa? Apparently, it was not easy. The weather was unbearable and the winds covered any signs of their path, leaving the guides lost. But, according to Plutarch (who relied heavily on Callisthenes - Alexander's official court historian), ravens intervened in this catastrophe and helped guide them to the oasis.

Arrian, in In The Campaigns of Alexander, also mentions two extraordinary accounts (one from Ptolemy and the other from Aristobulus) of how their group survived the trip and found Siwa. According to Ptolemy (one of Alexander's closest generals who became the ruler of Egypt after his death) snakes appeared once they became lost and led them to the oasis. Aristobulus, another friend of Alexander who later wrote a biography, tells a similar story as Ptolemy, but substituting the snakes for crows (Curtius also gives credit to the crows). Although the details vary, the implication is all of these stories is that Alexander and his men received some kind of supernatural/divine assistance.

Once they reached the Oasis, Alexander was immediately guided to the the Temple of the Oracle, where he was greeted publicly by the high priest. This greeting was a significant moment, as it may have been used to justify Alexander's later claims to be the son of Zeus-Ammon.

In Plutarch's version, Alexander was welcomed to the Temple by the high priest "on the god's behalf as a father greeting his son" (27). Curtius also says the high priest greeted Alexander as son, and explained to him that this designation was given by his father Jupiter (Zeus)" (4.8.25).

But did the high priest of Ammon really immediately declare Alexander to be the son of their premier god? Possibly, but Plutarch offers a compelling alternative:

"Others say that the priest, who wished as a mark of courtesy to address him in Greek with the words 'O, paidon' ['My son'], because of his foreign accent pronounced the last letter as a sigma instead of a nu and said it as 'O, pai Dios' ['son of Zeus'], and that Alexander was delighted at this slip of pronunciation, and hence the legend grew up that the god had addressed him as 'son of Zeus'" (27).

We will return to this disputed moment later.

After greeting him, the priest escorted Alexander only into an inner chamber in the Temple where he could communicate with the god alone.

It is unclear exactly how the actual communication unfolded. Normally, a group of "boat-bearers" carried a platform that displayed a glittering statue or image of Zeus Ammon. In this way, the god was treated much like a Pharaoh of Egypt. A person seeking a prophecy directed their question to this image of Zeus-Ammon, whose platform would then move and shake in response. The high priest alone could then interpret its movements into a coherent answer.

But Alexander was not a normal consultant of the Oracle. He was, by that time, one of the two most powerful people in the known world (along with the Great King Darius of Persia). In addition, he may have already been considered Pharaoh himself. Instead of addressing this writhing platform of Zeus-Ammon, he was supposedly able to speak to the god directly alone.

The precise way in which Alexander communicated with the god is debated. What's important is the following: (1) Alexander's conversation, however is may have taken place, happened in secret, and (2) he emerged from the chamber quite pleased with the result.

Plutarch, Curtius, Justin, and Diodorus all report that Alexander was told that Ammon, not Philip, was his true father. With slight variations, they also report that Alexander was told he would conquer the world and never be defeated. It's not hard to see why Alexander (who was still faced with Darius and the Persian Empire) would have liked these prophecies, especially if he considered the words of this particular oracle to be especially reliable.

But not everything Alexander learned during his private chat with Ammon is known. Plutarch references a letter, allegedly sent from Alexander to his mother Olympias, in which Alexander promises to reveal the contents of his conversation with the god to her alone once he returned to Macedon (27). Unfortunately, Alexander never made it back to Macedon. Whatever secrets Alexander wished to share with Olympias died with him.

Alexander did not linger in the oasis after his visit to the Temple of Ammon. With the primary purpose of their excursion fulfilled, he and his army left Siwah and returned to Egypt.

A view from inside the ruins of the Temple of Amun toward the surrounding oasis and desert.

Alexander, a Son of Zeus-Ammon

Had Alexander left Ammon and Siwah behind when he led his army out of Egypt, his strange detour in the Libyan desert would not have taken on such a significance among those seeking to understand the conqueror. Instead, however, he seemed to develop a special reverence for - if not an identification with - the part-Greek, part-Egyptian, and part-Libyan god.

Here are some of the instances in which Alexander was linked with Zeus-Ammon, according to the ancient sources:

Alexander ordered his subjects to refer to him as "Jupiter's (Zeus') son", although this caused significant tension among the Macedonian contingent of his army (Curtius, 4.7.30-32).

Alexander's wish to have his subjects prostrate (bow) before him was, in part, motivated by his status as the son of Zeus-Ammon (Arrian, Book 4 & Curtius, 8.5.5-6).

According to Alexander, he told Philotas about the oracle's acknowledgement that he was the son of Zeus-Ammon. But Philotas did not take this news positively (Curtius, 6.9.18). Later, when Philotas was on trial, he begged Alexander to consult Ammon as to whether he should be put to death (6.11.5-7).

Clitus the Black, a close friend of Alexander, told him in a drunken dispute that he had been more honest to his king than his "father" Zeus-Ammon had been in Siwah (Curtius, 8.1.42). Plutarch quotes Alexander as saying "And it is the blood of these Macedonians and their wounds which have made you so great that you disown your father, Philip, and claim to be the son of Ammon!" (50). Alexander killed Clitus in a rage shortly afterwards.

Hermolaus, another member of Alexander's entourage convicted and killed for the crime of plotting against him, referenced Alexander's desire to be worshipped and his repudiation of Philip as his father (Curtius, 8.7.13).

Upon reaching the Indian Ocean, Alexander made sacrifices in accordance with instructions he received from Ammon (Arrian, Book 6). It has been speculated that he viewed this achievement as the fulfillment of the oracle's prophecy that he would conquer the world.

When some of Alexander's troops insulted him at Opis, they alleged told him to continue alone with the help of only his father (Arrian, Book 7). They said this to mock his claim to the be the son of Zeus-Ammon.

After Hephaestion's death, Alexander sent an envoy all the way to Siwah to ask the god if his friend should be honored as a god or a hero (Arrian, Book 7).

Alexander allegedly wished that massive pyramid be built in Macedon to honor his father Philip (Diodorus, 18.4.5). A comparison to the pyramids of Egypt suggests Alexander associated his biological father Philip with his celestial father Zeus-Ammon.

By some accounts, Alexander wished to be buried at Siwah, the oasis home of the oracle of Zeus-Ammon (Justin, 15.5).

In the decades following Alexander's death, his successors minted coins featuring him with horns - a trait associated with Zeus-Ammon.

In the Alexander Romance, an ancient biography of Alexander imbued with many fantastical elements, Alexander refers to himself in letters as the son of Ammon.

In both Christian (Book of Daniel) and Islamic myth, the figure of Alexander the Great is depicted with horns. It is possible Alexander himself wore horns and robes associated with Ammon on rare occasions.

Not all of these bullet points can be taken as fact. But the mainstream view among modern historians is that Alexander did indeed begin associating himself with Zeus-Ammon after his visit to Siwah in 331 BCE. He also began asking for divine honors from some of his subjects.

Plutarch reports that, after his visit to Siwah, Alexander "assumed a manner of divinity" around non-Greeks, as though he was "fully convinced of his divine birth and parentage" (28). But Plutarch believed this divine persona to be just that - a performance: "...Alexander was not vain at all or deluded but rather used belief in his divinity to enslave others" (28). In other words, Plutarch believed Alexander used the rumor that he was a son of Zeus-Ammon to justify his immense authority, especially to the foreign peoples he ruled.

So, it's not a leap to accept that Alexander's consultation with the oracle represented some kind of turning point in his public persona, if not his own sense of identity. A few unanswered questions have stumped historians ever since:

Why did Alexander risk his entire campaign - not to mention his life - to consult the oracle?

Did Alexander really consider himself to be the offspring of Zeus-Ammon?

What secrets, if any, did Alexander learn during his private consultation with the oracle?

By beginning with the first question - about why Alexander sought out this oracle in the first place - we may be able to render the whole scenario less puzzling.

A silver coin produced under the reign of Lysimachus (297-281 BCE) which depicts Alexander the Great with the traits of Zeus-Ammon.

Alexander's Disputed Birth

The sources of antiquity list a number of reasons Alexander made his famous detour to Siwah. Here are the direct quotes:

Arrian, The Campaigns of Alexander:

"...Alexander found himself passionately eager to visit the shrine of Ammon in Libya. One reason was his wish to consult the oracle there, as it had a reputation for infallibility, and also because Perseus and Heracles were supposed to have consulted it...But there was also another reason: Alexander longed to equal the fame of Perseus and Heracles; the blood of both flowed in his veins, and just as legend traced their descent from Zeus, so he, too, had a feeling that in some way he was descended from Ammon. In any case, he undertook this expedition with the deliberate purpose of obtaining more precise information on this subject - or at any rate to say he had obtained it" (III).

Curtius Quintus Rufus, History of Alexander:

"...Alexander was nevertheless goaded by an overwhelming desire to visit the temple of Jupiter (Zeus) - dissatisfied with elevation on the mortal level, he either considered, or wanted others to believe, that Jupiter was his ancestor" (4.7.8).

Plutarch, Strabo and Diodorus also provide accounts of his trip, but say little about his reasons for going in the first place.

It's not surprising that Alexander - an avid fan of the ancient heroes - would have been inspired to undertake a journey by the deeds of Heracles and Perseus, two of the most celebrated figures of Greek myth.

But what about this other aspect? Why did Alexander have a "feeling", as Arrian reports, that he was descended from Zeus-Ammon? Would it explain his desperation to see the oracle at Siwah? There may be some clues in the legends about Alexander's birth.

Plutarch gives an overview of these fantastical stories. In one, Alexander's mother, Olympias, was impregnated by a thunderbolt which struck her womb (thunderbolts are a major symbol associated with Zeus).

In another, Philip found Olympias lying in bed with a giant serpent. Terrified of the sight, he sent an envoy to consult the Oracle at Delphi, who instructed Philip to honor the deity known as Zeus-Ammon. The implication is that this serpent, a manifestation of Zeus-Ammon, impregnated Olympias rather than Philip (2-3).

Although these supernatural claims about Alexander's birth have received a great deal of attention from those who embrace the mythic qualities of Alexander's biography, most historians consider them apocryphal (fabricated) stories invented after Alexander's visit to Siwah. There are a few reasons for this:

As far as we know, Alexander never referenced these stories during his life. This leads us to think he wasn't aware of them and that they began to circulate after his death.

The stories are very similar to those that appear in the Alexander Romance, a collection of myths about Alexander that include scenes of him riding on a hawk and visiting the underworld. The outlandishness of the stories is an obvious strike against their credibility.

Although Zeus was certainly a relevant figure to the royalty of Macedon, Zeus-Ammon had no connection to Alexander or his family until he visited the oracle in 331 BCE.

In all probability, these legends about his birth were developed retroactively to justify Alexander's claims of divine origin, embellish his growing legend after his death, or both.

But that leaves us with the question of why Alexander risked so much to get to Siwah. Should be take the ancient Greek and Roman biographers' explanations at face value? Or is there something we are missing?

As usual, Robin Lane Fox, Oxford historian and Alexander expert, helps fill in some of the missing context in his brilliant book Alexander the Great. He covers the entire Siwah affair with tremendous attention to detail and offers his own theory to explain Alexander's actions.

Robin Lane Fox's Theory

Robin Lane Fox (RLF) acknowledges at the onset of his essay on Siwah that not everything in the ancient sources can be relied upon: "Historically, the visit to Ammon's oasis has long been the victim of hindsight and legend and nowhere is this plainer than in the disputed motives for the expedition" (200).

Historian Robin Lane Fox consults with actor Colin Farrell on the set of "Alexander" in 2004. Director Oliver Stone credited Fox's work as one of his key resources in developing the film.

From there, RLF addresses one prevalent explanation that Alexander's desire to visit the oracle at Siwah stemmed from his coronation at Pharaoh in Egypt. In 4th century Egypt, a Pharaoh would have been worshipped as a "son of Amun" (Remember: Amun was the chief Egyptian god. Zeus was the chief Greek god. These gods were conflated by the Greeks into Zeus-Ammon). According to this explanation, Alexander sought out the oracle in the Libyan desert in order to learn more about his new status as the son of Amun.

RLF shoots this idea down for a couple of reasons: #1 - it's not even clear that Alexander was ever formally made pharaoh. Besides, even if he was, Alexander didn't seem to value the title very seriously, as it is not mentioned directly in the ancient sources at all.

#2 - even if Alexander was crowned pharaoh in Egypt, that would not necessarily lead him to be more interested in an oracle in Libya. The king of the Egyptian gods, Amun, had his own temples and high priests much closer to Memphis whom Alexander could consult. RLF elaborates below:

"Only in one posthumous Greek statue is Alexander ever shown with the crown and symbols of a Pharaoh; none of his friends or historians is known to have alluded to his kingship in Egypt at any other time, and it did not influence his life, any more than later, when he became king of Persia, did he show any grasp or concern for the equally holy doctrines of the god Ahura Mazda. And yet Siwah and his sonship of Zeus were to remain lively themes until the very last year of his reign when Egypt had been forgotten..." (213).

According to RLF, it was Alexander's Greek-ness, not his new ties to Egypt, which helps explain his venture:

"Siwah was not a convenient or obvious place to learn about the mystique of Amun, even if Alexander had set out with this in mind; it was the Delphi of the Greek East and as a Hellene, not as Pharaoh, Alexander would be curious about a god who was known and patronized by Greeks because of his truthfulness. Zeus Ammon at Siwah was the last available oracle of Greek repute before Alexander led his troops inland into Asia, and Alexander wished to consult him for this simple reason alone" (204).

But wishing to consult an oracle and risking one's life, and legacy, to do so is quite another. So what compelled Alexander to take such a dramatic and unexpected detour into the Libyan desert? RLF believes this trip wasn't quite as irrational and surprising as the ancient historians have led us to believe.

Curtius and Diodorus tell us that Alexander met with ambassadors from the Greek city of Cyrene while en route to Siwah, who brought him gifts and became his allies. Cyrene was a city on the Libyan (Mediterranean) coast, settled by Greeks in the 7th century, and was the primary hub of trade in the region at the time. The Greeks who lived there were the ones who bridged the gap of Libyan/Egyptian religion (Amun) with orthodox Greek religion (Zeus).

RLF believes that Alexander's westward path from Alexandria actually fit his normal pattern as a conqueror and that the Oracle of Ammon was probably not top of mind until he met with the leaders of Cyrene:

"...it was through Cyrene that the Greek world had first come to think highly of Ammon and it was surely the same city's envoys who first reminded Alexander of the god's existence. Very possibly, they did not mention the oasis until Alexander had taken up their offer, gone to visit their cities and reached the town of Paraetonium, 165 miles west of Alexandria and ten miles beyond a usual turning-off point for pilgrims to Siwah. If so, Alexander would have turned west not to consult the god but to follow his envoys from Cyrene and secure his frontier with Libya, an aim which is in keeping with his methods as a general. Only when strategy was satisfied did he think of a detour to Ammon, a familiar and truthful oracle" (204-205).

This is a compelling explanation that removes some of the mystery from the equation. The decision to visit Siwah didn't come on suddenly like some of the ancient historians imply. Rather, it happened organically based on Alexander's interaction with the peoples he encountered - they persuaded him to seek out the oracle. Whether he was familiar with Zeus-Ammon before then or not, Alexander's ties to Zeus through the royal family of Macedon along with his heightened religiosity and tolerance for risk made the trip inevitable.

A Turning Point

Robin Lane Fox presents a convincing analysis of Alexander's reasons for visiting Siwah in the first place. But how does he make sense of Alexander's experience there and his later association with Zeus-Ammon?

Like many others, he believes Alexander's experience at the oasis was a pivotal moment in his life. But it may not have been the private conversation with the oracle that mattered the most. Instead, it was Plutarch's account - of the high priest fumbling his introduction - that made the most impact.

As quoted earlier in this article, the high priest apparently greeted Alexander publicly as "Zeus' son" instead of "my son". Although the reason for this was clearly a mispronunciation, it was commonplace among traveling Greeks of the time to draw what they wished from these kinds of accident-prone interactions.

RLF goes into more detail on this subject in his book Traveling Heroes In the Epic Age of Homer. In it, he explains the simplistic connections Alexander and other 4th century travelers tended to draw between their own culture and that of foreigners. For instance, he references Alexander and his army's belief that the Greek hero-god Dionysus had visited a settlement in India they called Nysa. "Plainly they had half-understood these names from the replies of local people whom they questioned through interpreters..." RLF explains (178). He also suggests the landscape around Nysa, which featured quite a bit of ivy - a symbol of Dionysus - was critical to them coming to this conclusion.

Alexander's men, thousands of miles from home, proactively sought to insert their own religious legends into the lands and events happening around them. It did not take any kind of "proof" to convince them - a similar-sounding word or strange geological find was more than enough evidence.

In other words, for Alexander, a clear mistake on the part of the High Priest at Siwah would not necessarily have been discarded - especially if it was in agreement with his own pre-existing beliefs. Alexander may not have believed he was literally the son of Zeus before hearing that title spoken by the priest, but the idea was entirely in sync with the mainstream Greek religion of the time.

The heroes who Alexander idolized as a boy, like Achilles and Heracles, often had one immortal parent. Given Alexander's royal blood (which connected back to Heracles and Zeus) and his meteoric rise to power in the years preceding his Siwah adventure (he had already consolidated his rule over Greece and the Phoenician coast), it's not a stretch to think he was beginning to see himself as an equal to these heroes, if he hadn't all along. RLF helps bring together these various threads:

"The kings and heroes of myth and of Homer's epic were agreed to be children of Zeus: Alexander, like many, may have come to believe of himself what he had begun by reading of others. The belief was a Homeric one, entirely in keeping with the rivalry of Achilles which was Alexander's mainspring; if it had been latent when he entered Egypt, the traditions of the Pharaoh's divine sonship and the proceedings at Siwah's oracle could have combined to confirm it and cause its publication through Callisthenes* to the Greek world" (216).

*Callisthenes was Alexander's official court historian through most of his travels in Asia.

Furthermore, a recent trend may have influenced Alexander's desire to associate himself with a god. Mortals being elevated to a godlike status was not solely found with the divine heroes of the distant past. Lysander, a Spartan admiral of the 5th and early 4th centuries BCE, was worshipped as a god on the island of Samos and Dionysius II, a ruler of Syracuse in the 4th century, claimed to be Apollo's son.

Most importantly of all, Philip II of Macedon, Alexander's father, is cited as one of the first Greek kings to award himself a divine, or at least semi-divine, status. He famously included a status of himself along those of the Olympians at his daughter's wedding, which suggested to some he wished to be regarded as their equal. Philip also depicted himself with similar traits to Zeus on coins minted during his reign.

Although he did not claim to be directly descended from a god, Philip II helped set the stage for his son's relationship with Zeus-Ammon. Like so many other aspects of his life, Alexander appears to have merely picked up where his father left off.

The Probable vs. The Possible

In Robin Lane Fox's view, a "fortunate slip of the priest's tongue" served to confirm "a belief which had long been growing on him" (214) - that he was directly descended from Zeus. Although this belief is entirely explainable through Alexander's religiosity, royalty, and the example of his father, RLF seeks to incorporate the rumors of Alexander's divine birth into his theory.

He references a letter, supposedly sent from Alexander to his mother Olympias, in which Alexander promises to tell only her the secrets he learned from the oracle upon his return to Macedon. Strangely, RLF appears to give this alleged correspondence some credence while simultaneously acknowledging the tremendous prevalence of "fictitious correspondence in Alexander's name" (216).

It is tempting to follow these threads into the mists of Alexander's family dynamics. Olympias, by all accounts, was an enigmatic figure. An initiate of the secretive, orgiastic cult of Dionysus, she was prone to display bizarre, intimidating behavior (like lying in bed with snakes). She also had a major falling out with her husband, King Philip, during Alexander's childhood. Some even accused her of plotting her husband's assassination. RLF sees this tension as playing a role in Alexander's search for a divine father:

"Disappointed in her marriage or keen to assert her superiority over Philip's many other women, she might well have spread a story that her son was special because he owed nothing to Philip and was child of the Greek god Zeus" (215).

But one could just as easily argue that Olympias, a cutthroat defender of her place as Queen, would never have spread any rumor that suggested Alexander was not part of Philip's bloodline. This could have undermined his status as the rightful heir to the throne of Macedon.

Plutarch isn't sure what side to take on Olympias' gossip:

"According to Eratosthenes, Olympias, when she sent Alexander on his way to lead the great expedition to the East, confided to him alone the secret of his conception and urged him to show himself worthy of his divine parentage. But other authors maintain that she repudiated this story and used to say, 'Will Alexander never stop making Hera jealous of me?'" (Book 3)

The implication is that Alexander was spreading a falsehood that could offend the gods.

Did Olympias tell Alexander one thing and the public something different? One possibility is that Olympias did spread a rumor about Alexander's divine birth while Philip was alive, as a means to undermine him, but after Philip's death denied them in order to protect her son's rightful claim to the throne.

Zeus seduces Olympias, fresco by Giulio Romano, 1526-1534

Another possibility is that she had nothing to lose by suggesting Alexander was the son of Zeus (and later Zeus-Ammon). Zeus was, after all, the chief god of Olympus. As ridiculous as the claim may sound now, it may not have jeopardized Alexander's status as heir. Either he was the son of the king, or he was the son of the most powerful deity in their universe of gods - whichever option one accepted, it qualified Alexander to wear the crown of Macedon.

Despite these intriguing possibilities, I am weary about giving too much thought to Olympias' involvement in Alexander's claim to be a son of Zeus-Ammon. So much regarding this topic appears to have been added into Alexander's life retroactively - like the stories connecting him to Ammon at birth - in order to create a better storyline. It also seems to shift the entire conversation away from the context of Alexander's culture and campaign to the eccentricities of individual personalities. The Olympias of the Roman and Greek accounts may be a compelling character, but we know very little about her with certainty.

One can certainly paint a picture of Alexander's childhood in which a possessive, highly-competitive mother led him to question his ties to his polygamous, alcoholic, absentee father. Her knowledge of secret religious cults may have given such claims more credibility in a young Alexander's mind. Who knows - maybe Olympias was strange enough to even believe her own words. If she really did plant a seed in a young Alexander's mind that he was the son of divine being, rather than Philip, his encounter with the Oracle at Siwah could have finally given him certainty. By clearing up a source of confusion in his childhood, Alexander's trip to the oasis was a tremendous breakthrough in his self-identity. Is such a picture possible? Yes. But is it probable. I say no.

The most likely explanation for Alexander's relationship to Zeus-Ammon relies on the major points of context Robin Lane Fox provides. His inspiration to follow the dangerous road to Siwah did not spring out of a vacuum, but developed naturally as he consulted with the settlers of Cyrene and established the western borders of his African territory. There was no miraculous revelation at the Temple of Ammon, just a mistranslated greeting that Alexander used for his own purposes. His claim to be the son of Zeus-Ammon originated at this moment, but was fully congruent with the religious and political context of his age (even if it wasn't popular with many of his followers). Robin Lane Fox offers a bit more detail on what this context was exactly:

"The visit to Siwah had not been calculated for the sake of the result that came of it; it was both secretive and haphazard, but its conclusion is perhaps the most important feature in the search for his personality. 'Zeus', Alexander was later thought to have said, 'is the common father of men, but he makes the best peculiarly his own'; like many Roman emperors after him, Alexander was coming to believe that he was protected by a god as his own divine 'companion'...as son of god, a belief which fitted convincingly with his own Homeric outlook, in whose favorite Iliad sons of Zeus still fought and died beneath their heavenly father's eye" (217).

The other stuff - supernatural stories about Alexander's birth, allegations that Olympias claimed Alexander was a son of Ammon - were added later. That's the simplest and, for me, most probable explanation.

But I am reminded of one piece of evidence which this explanation has trouble accounting for: Arrian, typically regarded as the most accurate ancient source on Alexander's campaigns, writes that Callisthenes, Alexander's official court historian, claimed that "if Alexander was destined to have a share of divinity, it would not be owing to Olympias' absurd stories about his birth, but to the account of him which he would himself publish in his history" (4.10.2-3).

Callisthenes was adamantly opposed to Alexander's divine pretensions. If he really did claim what Arrian believes he did, it appears that Olympias did indeed spread stories about Alexander being conceived by a higher being. This would mean that her influence could have played a major role in all this, both in what Alexander believed about himself and how he interpreted his meeting with the Oracle of Ammon.

For Robin Lane Fox, this brief passage in Arrian is "proof" that Olympias claimed to possess secrets involving the identity of Alexander's father. I don't have nearly the same sense of certainty that he does. But I do acknowledge that there may be far more to the story than we are able to understand from our limited sources. When it comes to Alexander, one can hardly ever escape the mystery - and legend - altogether.

Please leave any comments or questions below. Thanks for reading.

Main sources:

Arrian, Campaigns of Alexander

Plutarch, Life of Alexander

Curtius, History of Alexander

Robin Lane Fox, Alexander the Great

Robin Lane Fox, Traveling Heroes in the Epic Age of Homer